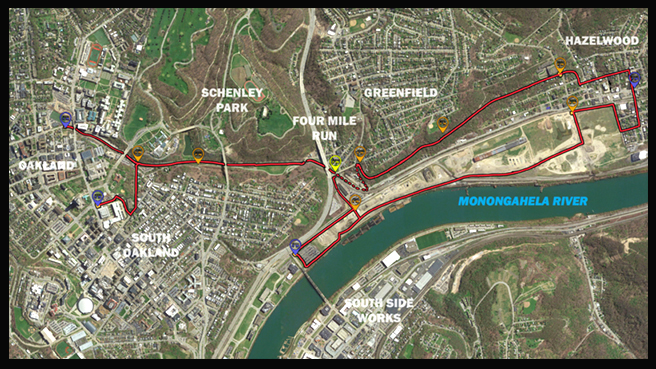

The proposed route of the controversial Mon-Oakland Connector project

An OPN News Special Report

The History

An August 29, 2015 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette article announced the Oakland-Transit Connector project, since renamed the Mon-Oakland Mobility Plan or Mon-Oakland Connector (MOC). Using driverless shuttles, the proposed roadway would cart students and university personnel every 5 minutes between Oakland campuses and the Hazelwood Green (HG) development site—running through the Junction Hollow portion of Schenley Park and the neighborhoods of Panther Hollow and Four Mile Run (The Run) at either end. The article announced the plan as a “done deal,” but city officials and private partners held closed-door meetings to plan the project without consulting or even informing residents—a violation of Pennsylvania’s Sunshine Act. The roadway announcement kicked off an uprising from the two neighborhoods in its path.

The project’s unveiling showed a public-private partnership formed between the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA), Pitt, and CMU filed a grant application with the State of PA Department of Community and Economic Development (DCED). In response to a resident’s Right to Know (RTK) request, the URA provided a copy with missing pages, but residents had already received a complete copy from the DCED in Harrisburg that exposed numerous falsehoods. Although the grant app states “the act of knowingly making a false statement or overvaluing a security to obtain a grant and/or loan from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania may be subject to criminal prosecution,” Allegheny County District Attorney Stephen Zappala failed to return resident phone calls and emails and never responded to a hand-delivered letter to his office requesting an investigation.

Opponents say the MOC will not improve transportation for the public or residents of Hazelwood and would permanently degrade Schenley Park and both communities along the route. In spite of a large and growing opposition throughout surrounding neighborhoods, and a projected $100+ million deficit this year due to the economic effects of COVID-19, local officials and their private partners have insisted on pushing through the publicly subsidized, $23 million private development project, come Hell or high water.

The High Water

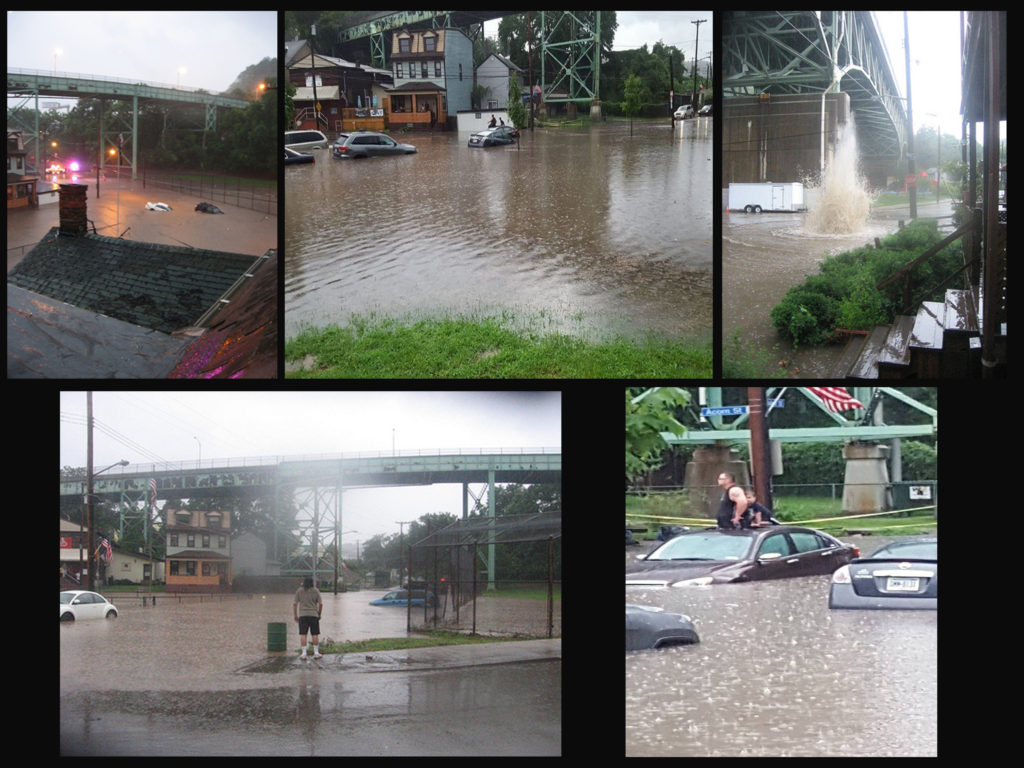

Run residents have suffered from chronic flooding for many years, yet were repeatedly told the City lacked funds to stop the heavy stormwater mixed with raw sewage that has become more frequent and severe over time. An August 2016 flood captured on video, showing firefighters rescuing a resident and his young son from the roof of their car, received long overdue press coverage and forced city officials to publicly acknowledge the issue. They announced a $40 million plan headed by the Pittsburgh Water and Sewer Authority (PWSA). But over the adamant objection of residents, city officials insisted the MOC was to be forced onto the 4MR Watershed Improvement Plan.

Expert sources in infrastructure/flood mitigation have told residents that including the MOC could harm flood control and residents have made repeated requests for the “comprehensive detailed hydraulic flood mitigation model(s),” but the city has yet to prove that forcing the roadway onto the flood plan will not harm flood control.

In response to RTK requests filed in 2019, minutes from a meeting at the Mayor’s office show Mayor Peduto’s chief of staff Dan Gilman “wondering if instead of a 25-year storm which is what current development designs for, should we be designing for a larger storm event?” But the PWSA’s flood mitigation plan presented on June 18, 2020, scaled down to a 10 year plan while telling residents it was sufficient for their neighborhood that frequently experiences 25- and even 75-year floods.

Residents have repeatedly asked PWSA if they had produced or will produce a flood mitigation model that does not include the MOC. In an email reply to the question, PWSA stated they haven’t because they were not directed to do so. But a PWSA official revealed on September 15 that they did produce a flood mitigation model without the MOC roadway—the first model they produced. PWSA has been in charge since 2017, so why has the PWSA repeatedly stated they did not?

Questions at the September 15 PWSA stormwater meeting included, “Using the same circumstances and conditions of the 2009 75-year flood event—and after construction of the 10-year flood plan—how many inches or feet of water and sewage can residents expect to have in their basements?” PWSA gave an estimated reduction of 45%. This translates to about 38 inches of water and sewage in residents’ homes. PWSA claims this is an acceptable, “cost-effective” result of their flood mitigation plan.

RTK requests filed with PWSA in June of 2020 brought a retaliatory response: Residents were given a 7,185-page unsearchable PDF document, which begs the questions: If officials are certain of the effectiveness of their flood mitigation plan, why not provide all requested documents without the need to file RTKs? Why erect roadblocks and hurdles to the truth about the MOC and its possible effect on flooding in the neighborhood?

According to resident Ziggy Edwards, “In The Run, we need the watershed improvement plan to work. We don’t need to spend tens of millions of our tax dollars on a shuttle roadway that may hinder flood relief and eventually wipe two historic neighborhoods off the map.”

The Circular Excuses

Reasons for constructing the MOC continually shift. At one point the project was pitched as a “proof of concept” for autonomous vehicle shuttles. But in July of 2019, Pittsburghers for Public Transit produced a position paper titled “Wait, Who’s Driving This Thing?” showing that AV feasibility is 30 years away, causing the city to respond, “There is no such thing as an autonomous vehicle,” and claim they are abandoning the AV element. Other reasons given for the MOC include:

• “Economic development and job creation” – Opponents have repeatedly asked for a list of jobs that will result from the roadway, but the city has never produced a list or responded to the question.

• “It’s needed for people to travel the route on e-bikes and e-scooters” – The existing Junction Hollow Trail already provides for those alternate forms of transportation. Filling in a few gaps along the existing route, as identified and suggested by the Southwestern PA Commission, would improve public mobility at a much lower cost.

• “Hazelwood residents need a faster route to Oakland to get to grocery stores, doctors’ offices, and hospitals” – The MOC will not save time, Oakland does not have a supermarket, and taking a 15 mph shuttle to Oakland would not save a life if seriously injured. Opponents say a better use of public money for revitalization would be a supermarket, doctors’ offices, and an urgent care facility in Hazelwood.

• “It may not even include shuttles!” – Then why build a $23 million shuttle roadway? (An RTK document shows Don Smith of RIDC development group stating, “Let’s get an imperfect connector road there now and more perfect long-term solution implemented later.”)

• “It’s good for Hazelwood because it’s good for Hazelwood Green” – This reasoning evokes “trickle-down” economics, but even Mayor Bill Peduto knows most people never benefit from this economic model, as evidenced in his recent Tweet: “Mid-sized & smaller cities, who have taken on the expenses & lost the revenue, are being told no relief in sight. Yet extremely wealthy & politically connected are being handed 100s of millions. This will never bring back our economy. It has never trickled down to the people.”

A comprehensive study by Tech4Society (T4S), A People’s Audit of the Mon-Oakland Connector, shows that the shuttle would not save time and would come at a much greater cost than the Our Money. Our Solutions. alternative plan proposed by the neighborhoods of The Run, Panther Hollow, Greenfield, and Hazelwood. The resident-driven plan addresses their long-neglected infrastructure and transportation needs.

Bonnie Fan, a T4S researcher states, “We examined the City’s arguments in favor of the Mon-Oakland Connector and found that a similar service could be provided with shuttle consolidation between the universities and UPMC, that the Connector would barely serve the projected [Hazelwood Green] ridership, and that it provided no travel time benefits compared to transit improvements from Our Money. Our Solutions.”

Trickle Down Economics “The principal that the poor,who must subsist on table scraps dropped by the rich, can best be served by giving the rich bigger meals.” —William Blum

The Degradation of the Park

The existing Junction Hollow Trail/Three Rivers Heritage Trail is the only route that allows bicyclists and pedestrians to travel between Oakland, Greenfield, Hazelwood, South Side, and Downtown without sharing space with motorized vehicles. A soccer field and practice area along the trail is in frequent public use by athletes of all ages, and is an especially popular spot for youth soccer. Families, hikers, bikers, runners, commuters, and dog walkers all use the trail—and the park is home to many indigenous species of western PA wildlife.

Despite residents proposing existing alternative routes that would bypass the park and their neighborhoods, City officials have insisted the only viable route was through Schenley Park. But RTK documents reveal Department of Mobility and Infrastructure (DOMI) Director Karina Ricks stating that the MOC is not a transportation solution and indicating other routes would have to be used—the very same resident-proposed routes derided by city officials as non-viable.

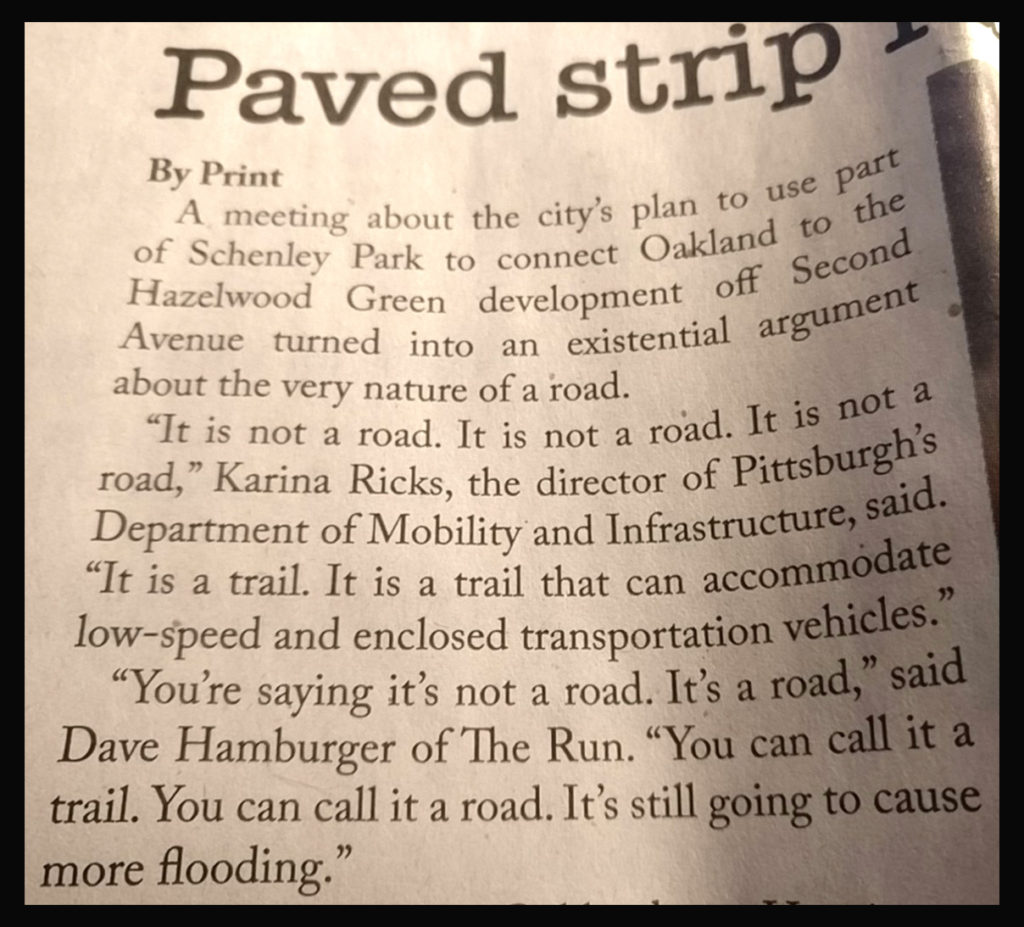

At a packed and contentious November 2019 public meeting, attendees from various Pittsburgh neighborhoods, including Squirrel Hill, Hazelwood, Greenfield, and The Run, vehemently denounced the roadway project. At one point, DOMI Director Ricks interrupted the meeting, trying to defend the construction of the road through Schenley Park by declaring, “It is not a road! [repeated twice more] It is a trail! It is a trail that can accommodate low-speed and enclosed transportation vehicles.”

“The very idea that the City wants to allow vehicles on the path where we walk, run, and bike is incomprehensible to me,” said Greenfield Community Association Board member and Run resident Barb Warwick. “CMU and Pitt want to run their shuttles steps away from the field where our kids play soccer—and Peduto and City Council are just letting them do it. It’s total disregard for our neighborhood and our kids’ safety. Schenley Park belongs to the people, not the universities.”

The $63 Million Question

$40 million for a Stormwater mitigation plan that doesn’t fix the chronic flooding and $23 million for a roadway through a park that is not a transportation solution raises many important questions, including one at the root of it all:

While the current pandemic has devastated our city’s economy for years going forward, and Mayor Peduto stating that all major development projects should be put on hold for several years, why are city officials so determined to bulldoze through two healthy neighborhoods and Schenley Park when evidence shows that their proposed shuttle roadway is non-essential?

“That’s what I want Peduto to tell us,” said Ms. Edwards. “Why is it so important to get 15-mile-per-hour vehicles through Schenley Park? Why do they have this unwavering commitment to spend $23 million out of the city’s capital budget on a road, even though they’ve had to admit it won’t meet a single one of their stated goals? It’s not a more efficient transportation solution than bus service and it doesn’t help existing residents get around better.”

The Reveal

Documents received through numerous RTK requests, along with statements and actions by proponents of the MOC, reveal many concealed truths—including Mayor Chief of Staff Dan Gilman referring to the overall 4MR Watershed project that presently includes the MOC as “a clusterf@$k.”

In October 2017, a source in the Pittsburgh Parks Conservancy stated that the roadway “has to happen” because “no one will sign onto it [the development] unless it’s built.” And in October of 2018—when directly asked by Run resident Kristen Macey, “Why is putting this roadway in so important to you?” County Executive Rich Fitzgerald answered, “This isn’t for you; this is for the universities to get down to the Hazelwood [Green] plan.”

A “Mayors Meeting Minutes” RTK document reveals Heinz Endowment (owners of the HG site) representatives stating: “The connector road to Oakland is incredibly important. Developers have indicated their interest in the Almono site is contingent on the road being constructed.” The roadway project is indeed a sign-on condition for potential HG developers and tenants, rather than a necessity that would serve the affected communities and public.

“The Mon-Oakland Connector fails as a transit project,” says Laura Wiens, executive director of Pittsburghers for Public Transit. “The resident-led Our Money. Our Solutions. alternative transportation plan is far more effective than the MOC across all key metrics—speed, ridership capacity, cost, accessibility, the impact to the natural environment, and impact to housing affordability in the corridor. $23 million in public money should be used to meaningfully address transportation barriers in Hazelwood, Greenfield, and Oakland, and not advance private development agendas that push residents out.”

The Multibillion-dollar Answer

Essentially, the public is expected to pay for the MOC so that the multibillion-dollar non-taxable entities and others who stand to profit from the roadway… can profit from the roadway. The roadway would provide the sign-on condition demanded by universities—a publicly financed private driveway to the private HG site from Oakland campuses. And it would establish a beachhead for university expansion by seizing a portion of Schenley Park and commandeering neighborhood streets and green space with the eventual goal of erasing two healthy communities along the route.

DOMI has already begun changing street signs in The Run/Lower Greenfield in an attempt to rename Swinburne Street and Swinburne Bridge to Frazier Street and Frazier Street Bridge. Frazier Street exists about a half mile outside The Run in nearby Oakland.

Evidence shows that the Mon-Oakland Connector project is a Trojan horse—the first step in an attempted massive land-grab by Oakland universities and other private interests for profit-seeking expansion and “growth” through premeditated community erasure.

The Op-Ed

“Growth for the sake of growth is the ideology of the cancer cell”—Edward Abbey

A 2017 city-mandated survey in The Run shows an overwhelming majority of residents adamantly opposed to the roadway and unanimous demand for effective flood relief. Residents reached clear consensus on their community’s needs through true democratic process, but city officials continue governing via crony capitalism. Deals made behind closed doors are inherently non-transparent and undemocratic—and break the regulations surrounding any development plan that state public officials have an obligation of transparency with full public vetting before any decisions are made. Development plans must have the affected community’s approval, and residents have every right to veto any project that would harm their community—because democracy does not end at the ballot box, it only begins there. If growth for the sake of growth is the ideology of the cancer cell, Pittsburgh city officials are cancer-causing agents.

As city officials and their private partners continue driving down a path toward confrontation with opponents of the roadway, it’s worth pointing out the similarities between the MOC project and attempts to build oil pipelines through sacred indigenous lands. For residents of The Run, their historic community is sacred, and they “refuse to be a sacrifice zone for private development through predatory land speculation and gentrification.” They have vowed to protect Schenley Park as well as their community.

Every justification put forth for building the MOC has been proven false. Proponents now seem to be at a loss for any argument other than, “We have to build it because we’ve been secretly planning this behind closed doors for years!” This may be the heart of the matter regarding the MOC:

• Do elected officials have the right to rule by decree, including striking secret deals that will erase whole communities off the map for profit for their campaign contributors—the privileged and well-connected few?

• Does a healthy, vibrant Pittsburgh neighborhood have the right to decide its own future, or should it be forced to allow shady back-door development deals to erase their community for privatized profit?

“Schenley Park belongs to the people, not the universities” – Greenfield Community Association Board member Barb Warwick

The Stand

Run residents continue to file RTK requests for hidden details on the MOC and flood-mitigation plans, hold community marches and press conferences, produce multimedia and lobby City Council among other actions to stop the construction of the MOC. A grassroots, multi-community coalition has grown to include social justice organizations, neighborhood associations, churches, community groups, and others aligning with residents in opposition to the MOC and calling on City Council to reallocate MOC funding to their community-generated Our Money. Our Solutions. plan. Opponents say providing money for neighborhood revitalization need not include tens of millions in city resident money for multibillion-dollar tax-exempt institutions. Although city officials continue to ignore the communities’ plan, Allegheny County Port Authority has already agreed to an important part of it: adding weekend bus service to the 93 Hazelwood route—improving mobility for Hazelwood residents in reality, not a deceptive PowerPoint presentation.

Opponents of the MOC are asking the public to join them in rejecting secret deals made by local government officials, and to organize their own communities to participate in a true democratic process for citywide grassroots community development.

If you’d like to support residents in opposition to the MOC, sign the petition at https://actionnetwork.org/petitions/our-money-our-solutions.

And for more information, visit junctioncoalition.org.